It was the doing of the most principled of US Attorney Generals

By Dan Gifford

Kansas Republican Congressman Roger Marshall has drafted a bill to free short barreled rifles — those with barrels less than 16 inches — from National Firearm Act (NFA) restrictions that require purchase of a federal license and registration. That has been the case since 1934 when the NFA was put on the books in response to media and political hyperventilations about gangster violence of the time. In the absence of Trump in the White House backed by libertarian Republicans in total control of Congress, it’s doubtful Marshall’s bill has even a snowball’s chance in hell of passage, but it’s at least a worthy college try to rid the law books of an unneeded statute.

Long before “assault weapons” and “weapons of war” were the concocted labels used by our uninfringible First Amendment protected media to frighten the public into infringing on Second Amendment rights, “Gangster guns” was the scary phrase in play.

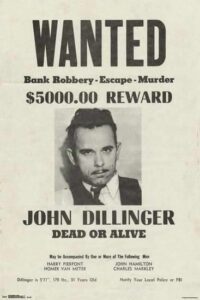

They were defined by those era pundit H.L. Mencken called the social reform “uplifters” as the machine guns, short barreled shotguns, rifles and the handguns used by criminals like Bonnie and Clyde, John Dillinger, Pretty Boy Floyd and others. They were also the guns millions of Americans owned and used for non criminal purposes. But like today, the media created perception was that they were only used by criminals.

That false reality was hugely publicized in conjunction with their outlaw 1930s era gun play and that of the roaring 20s Chicago gangs.

The 1929 Saint Valentine’s Day Massacre of the North Side Mob by Al Capone gunmen received national front page coverage and freaked the nation.

But the earlier 1926 attempt by North Side gangsters to kill Capone had also caused a panic. That one featured some 10 cars full of mobsters who did a drive by machine-gunning of the Hawthorne Hotel restaurant in Cicero (a Chicago suburb) where Capone was having lunch.

Impotent to do anything about the gangs themselves that paid off both police and politicians for protection, citizens like these three at a 1924 Cicero polling place had to arm themselves to protect voters against mob violence and intimidation.

This photo shows Cicero Chief of Police Albert W. Valecka with one of hundreds of people injured by roving bands of mob “slugger” thugs who intimidated, beat up and even kidnapped voters, election workers and campaign workers on election day.

Even so, do gooder activists of the day — Mencken’s “uplifters” — demanded the “gangster guns” be banned. Banned? Like today, gun bans were not a popular idea outside of the elite “uplifter” class.

The social reformers at Nation magazine had discovered that during the 1920s when they advocated a ban on the civilian possession of revolvers that was to expand to include all privately owned firearms. A probable reason for the amount of both public and pundit opposition was that Americans then still understood why there was a Second Amendment guarantee of a right to arms.

Most every schoolboy then knew the Second was intended to assure an armed population that could oppose foreign invasion, usurpation of power by rulers and provide personal self protection against the downside of the most dangerous rights of all. those are the rights of due process that often make it impossible to arrest and convict vicious criminals.

So until the National Firearm Act was put on the books in 1934, anyone could buy a “gangster gun” or any other sort of firearm at practically any hardware store or by mail with no questions asked. The 1934 Chicago Tribune editorial board was among those who understood what too many no longer do, including today’s Chicago Tribune.

“In the revolutionary war the people were able to gain their liberties because when they tried for them possession of firearms was common and many of the citizens knew how to use them. A disarmed population of people familiar with weapons would not have had much chance. In 1789 the weapons in general use would be long rifles, muskets, and clumsy pistols. The people were entitled to have the best weapons they could make or purchase. Now the best weapons for individuals are machine guns and automatic rifles. Use which can be made of these is indicated by law, but it is not the possession of which is properly an offense under the constitution.”

“It is notorious that when restrictions are put upon the possession of firearms or any particular kind of weapon they never are effective against the criminal classes but only put the peaceable man at a disadvantage or in a false position before the law. The prohibition does not bother the enemy of society but it makes a technical offender of the decent citizen. The man who would not misuse a weapon is the man who is injured. The drive for public security is thus given the wrong direction.” That’s where the man I consider to be one of the most principled lawmen stepped into the fray.

That man was Homer Cummings, U.S. Attorney General. He told the Congressional uplifters they had no constitutional authority to ban firearms because doing so would violate the Second Amendment. That made many on Capital Hill unhappy with him and his Solomon like compromise of a $200 NFA tax and gun registration indicating the tax had been paid instead of a ban. But Cummings had the cajones to stand his ground.

He’d been in that position before in 1924 as District Attorney of Bridgeport, Connecticut when he faced down both community and police lynch level anger against the murder suspect of a beloved local priest in that overwhelmingly Catholic town.

As shown in this scene from the 1947 film “Boomerang!” about case, Father Hubert Dahme died from a single shot to the head while taking his usual downtown evening stroll. The gunman was a total stranger who immediately ran off.

Several weeks later, police arrested a vagrant named Harold Israel who fit the killer’s description. Israel was found to be carrying a loaded revolver of the same caliber that killed Dahme. But that wasn’t all. The revolver had a fired cartridge case in one chamber.

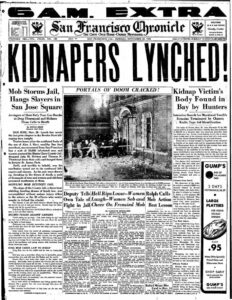

Witnesses on the sidewalk to the murder quickly identified Israel as the killer. Bridgeport’s police forensics expert said the bullet taken from Dahm matched those test fired in the drifter’s gun. Shortly after, Israel confessed to the murder after being worked over by police interrogators. Nothing unusual for that time. Confessions were commonly coerced or beaten out of suspects then and the practice continued well into the 1960s. Incited by the newspapers about such convincing evidence, Bridgeport mob anger was sufficient to dispense with a trial and string Israel up as would actually be done later to two kidnapping suspects in 1933 San Jose, California.

But as the trial date approached, Cummings conversations with the accused man caused him to sense something wasn’t right. So he rechecked the evidence. What Cummings found should give anyone pause who’s in a rush to judgment.

Cummings had both the bullet and the revolver reexamined by six different forensics experts. He interviewed all of the witnesses to the shooting. He stood where they stood and had them explain what they said they saw. The result was that the witnesses could not have seen what they claimed and the forensics examiners found the bullet that killed Father Dahme came from a different revolver than the one Israel was carrying. None of that meant charges were dropped. Cummings still had to go through with the trial to assuage the angry public. However, at that trial, Cummings did not prosecute Israel, he prosecuted his own evidence — the state’s own case — against Israel and disproved it.

Cummings’ actions so moved renowned Supreme Court justice Felix Frankfurter that he said what Cummings did “will live in the annals as a standard by which other prosecutors will be judged.” And it has, providing a historical counterpoint to the present day, when stories abound of prosecutors who do anything to win a conviction by putting politics above principle.

It’s difficult to understand today just how radical Cummings’ action was. Little had been written at the time about false confessions, mistaken eyewitnesses, police perjury, withheld exculpatory evidence or the large number of bogus forensics like those revealed at the FBI by its own crime lab supervisor, Dr. Frederic Whitehurst. The system was assumed to be infallible. So much so, that the year before Israel’s arrest, Learned Hand, an esteemed federal judge in New York, dismissed the very idea that an innocent person could be convicted, calling it “an unreal dream.”

That may be what what Congressman Marshall’s legislation amounts to as well. Even if Donald Trump is reelected and Republicans solidly control both houses, the deep states of academia, politics, police and media will oppose Marshall’s measure and stand a highly probably chance of kiboshing it.

—

Dan Gifford is a national Emmy-winning,

Oscar-nominated film producer and former

reporter for CNN, The MacNeil Lehrer

News Hour and ABC News.

###