By Dan Gifford

22 May 2010

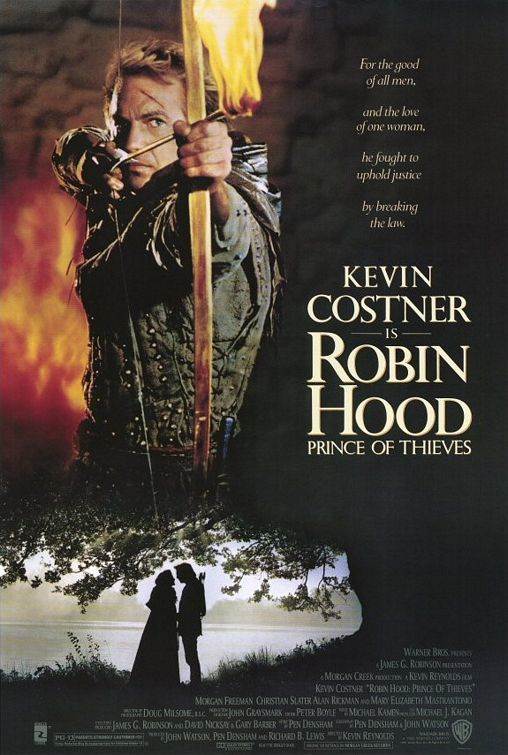

Robin Hood is back on the big screen in his umpteenth adaptation and

he’s not only fighting social injustice by robbing the rich and giving

to the poor, he’s fighting it by forcing English King John the cruel to

sign the Magna Carta. More on that later. For now, let’s stick with the

redistribution of wealth by banditry.

People love that idea. And because they do, Robin has had a massive

influence on popular culture because the implicit anti-establishment

message in his story can be used as a device to criticize society or

sell almost any social movement, legislation or outright criminal

activity in modern societies that have no relation to the brutal feudal

times in which his legend originated. The result, the Sherwood Forest

outlaw can be anything one wants him to be.

A Robin who “robs the rich to give to the poor” can be that mythical

Marxist revolutionary or populist hero righting the wrongs of capitalism

for the oppressed proletariat — even if he happens to be nothing

People love that idea. And because they do, Robin has had a massive

influence on popular culture because the implicit anti-establishment

message in his story can be used as a device to criticize society or

sell almost any social movement, legislation or outright criminal

activity in modern societies that have no relation to the brutal feudal

times in which his legend originated. The result, the Sherwood Forest

outlaw can be anything one wants him to be.

A Robin who “robs the rich to give to the poor” can be that mythical

Marxist revolutionary or populist hero righting the wrongs of capitalism

for the oppressed proletariat — even if he happens to be nothing

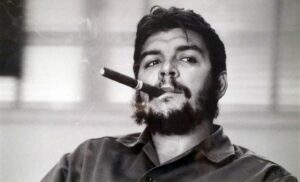

more than a mass murdering rapist like Che Guevara:

more than a mass murdering rapist like Che Guevara:

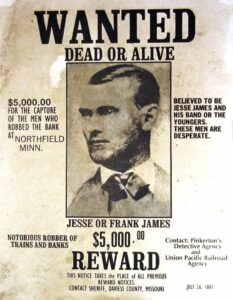

or a common stick-up guy like Jesse James

or a common stick-up guy like Jesse James

or a 1930s bank robber with a heart like Pretty Boy Floyd,

that Woody Guthrie lionized in song:

Many a starving farmer

The same old story told

How the outlaw paid their mortgage

And saved their little homes

Looked at another way, a Robin who’s robbin’ the rich of onerous taxes

they have forced on productive workers to support their bloated

government might be one of Grover Norquist’s Americans for Tax Reform

conservatives.

Toss in Robin’s opposition to the oppressive King John, who has usurped

the crown of his brother Richard I and sicced ye Sheriff of Nottingham

on those who question his authority to enact ruinous taxes, and you have

the makings of America’s revolutionaries who went to war over the

legitimacy of British taxation sans representation.

Emphasize the ruling Norman oppression of conquered Saxons that is

themed in Ivanhoe, the 1800s Sir Walter Scott book that popularized the

Robin Hood character in the first place, and you’ve got a story about

racism and intolerance even if Al Sharpton wouldn’t agree ’cause they’re

all white folks.

That’s why different versions of the story among the scads that have

been filmed through the years have been used by their makers to touch

different cultural and political nerves.

or a 1930s bank robber with a heart like Pretty Boy Floyd,

that Woody Guthrie lionized in song:

Many a starving farmer

The same old story told

How the outlaw paid their mortgage

And saved their little homes

Looked at another way, a Robin who’s robbin’ the rich of onerous taxes

they have forced on productive workers to support their bloated

government might be one of Grover Norquist’s Americans for Tax Reform

conservatives.

Toss in Robin’s opposition to the oppressive King John, who has usurped

the crown of his brother Richard I and sicced ye Sheriff of Nottingham

on those who question his authority to enact ruinous taxes, and you have

the makings of America’s revolutionaries who went to war over the

legitimacy of British taxation sans representation.

Emphasize the ruling Norman oppression of conquered Saxons that is

themed in Ivanhoe, the 1800s Sir Walter Scott book that popularized the

Robin Hood character in the first place, and you’ve got a story about

racism and intolerance even if Al Sharpton wouldn’t agree ’cause they’re

all white folks.

That’s why different versions of the story among the scads that have

been filmed through the years have been used by their makers to touch

different cultural and political nerves.

I grew up watching “The Adventures of Robin Hood,” starring Richard

Greene during the 50s without ever realizing its stories about the

exploitation of serfs and ill gotten capitalist wealth were written by

blacklisted communist Hollywood writers who were spreading Soviet agitprop.

Neither did I know that Robin’s paranoia about betrayal to the

authorities was what the pseudonymed writers of those stories worried

about lest their propaganda jig be up. “The Adventures of Robin Hood

gave us plenty of opportunities to comment on issues and institutions in

Eisenhower-era America,” admitted writer Ring Lardner, Jr.

I grew up watching “The Adventures of Robin Hood,” starring Richard

Greene during the 50s without ever realizing its stories about the

exploitation of serfs and ill gotten capitalist wealth were written by

blacklisted communist Hollywood writers who were spreading Soviet agitprop.

Neither did I know that Robin’s paranoia about betrayal to the

authorities was what the pseudonymed writers of those stories worried

about lest their propaganda jig be up. “The Adventures of Robin Hood

gave us plenty of opportunities to comment on issues and institutions in

Eisenhower-era America,” admitted writer Ring Lardner, Jr.

“The Story of Robin Hood and his Merrie Men” was also done during the

50s but its maker, the anti-communist Walt Disney, emphasized the

ruinous taxation imposed by an oppressive King John at a time when

America’s top bracket was 90%.

“The Story of Robin Hood and his Merrie Men” was also done during the

50s but its maker, the anti-communist Walt Disney, emphasized the

ruinous taxation imposed by an oppressive King John at a time when

America’s top bracket was 90%.

1938’s “The Adventures of Robin Hood” starring Errol Flynn is the

only version I’ve seen that really focuses on the oppression of

the Saxons by the French speaking Norman rulers who won the 1066

Battle of Hastings.

1938’s “The Adventures of Robin Hood” starring Errol Flynn is the

only version I’ve seen that really focuses on the oppression of

the Saxons by the French speaking Norman rulers who won the 1066

Battle of Hastings.

The Normans were really French speaking Vikings. And the England William

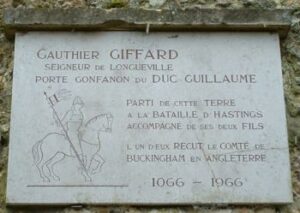

of Normandy and his cousin -- and my ancestor -- Gauthier Giffard fashioned was one in which

the Saxons and other subjugated peoples like the Welsh sucked hind teat

in ways we today cannot begin to imagine. Against that blackness,

robbing those who had taxed the common man to the edge of existence in

many cases was both moral and necessary.

The Normans were really French speaking Vikings. And the England William

of Normandy and his cousin -- and my ancestor -- Gauthier Giffard fashioned was one in which

the Saxons and other subjugated peoples like the Welsh sucked hind teat

in ways we today cannot begin to imagine. Against that blackness,

robbing those who had taxed the common man to the edge of existence in

many cases was both moral and necessary.

Translation of plaque at Castle Giffard, Normandy: "Gauthier Giffard,

Lord of Longueville carried the Banner of the Duke William. Departed

from this land to the Battle of Hastings accompanied by his two sons,

one of whom became the Duke of Buckingham."

Over time, Norman nobles started getting the short end of the stick too.

That boiled over under the harsh and inept rule of King John (known as

“Soft Sword” for his military incompetence) to the point that the barons

forced John to sign a bill of rights against absolute royal power known

as the Magna Carta.

What I’ve never seen depicted is that those rights only applied to the

nobility, that John refused to honor them, that he had the leaders of

the Magna Carta barons killed, and that England plunged into years of

bloody war between the barons and the king.

Did Robin Hood really exist? Certainly not as he’s been portrayed — if

at all. But that doesn’t really matter, because the real importance of

Robin Hood is that he’s an inspiration for taking a stand against

injustice however one defines it.

---

Dan Gifford is a national Emmy-winning,

Oscar-nominated film producer and former

reporter for CNN, The MacNeil Lehrer

News Hour and ABC News.

Translation of plaque at Castle Giffard, Normandy: "Gauthier Giffard,

Lord of Longueville carried the Banner of the Duke William. Departed

from this land to the Battle of Hastings accompanied by his two sons,

one of whom became the Duke of Buckingham."

Over time, Norman nobles started getting the short end of the stick too.

That boiled over under the harsh and inept rule of King John (known as

“Soft Sword” for his military incompetence) to the point that the barons

forced John to sign a bill of rights against absolute royal power known

as the Magna Carta.

What I’ve never seen depicted is that those rights only applied to the

nobility, that John refused to honor them, that he had the leaders of

the Magna Carta barons killed, and that England plunged into years of

bloody war between the barons and the king.

Did Robin Hood really exist? Certainly not as he’s been portrayed — if

at all. But that doesn’t really matter, because the real importance of

Robin Hood is that he’s an inspiration for taking a stand against

injustice however one defines it.

---

Dan Gifford is a national Emmy-winning,

Oscar-nominated film producer and former

reporter for CNN, The MacNeil Lehrer

News Hour and ABC News.

People love that idea. And because they do, Robin has had a massive influence on popular culture because the implicit anti-establishment message in his story can be used as a device to criticize society or sell almost any social movement, legislation or outright criminal activity in modern societies that have no relation to the brutal feudal times in which his legend originated. The result, the Sherwood Forest outlaw can be anything one wants him to be. A Robin who “robs the rich to give to the poor” can be that mythical Marxist revolutionary or populist hero righting the wrongs of capitalism for the oppressed proletariat — even if he happens to be nothing

more than a mass murdering rapist like Che Guevara:

or a common stick-up guy like Jesse James

or a 1930s bank robber with a heart like Pretty Boy Floyd, that Woody Guthrie lionized in song: Many a starving farmer The same old story told How the outlaw paid their mortgage And saved their little homes Looked at another way, a Robin who’s robbin’ the rich of onerous taxes they have forced on productive workers to support their bloated government might be one of Grover Norquist’s Americans for Tax Reform conservatives. Toss in Robin’s opposition to the oppressive King John, who has usurped the crown of his brother Richard I and sicced ye Sheriff of Nottingham on those who question his authority to enact ruinous taxes, and you have the makings of America’s revolutionaries who went to war over the legitimacy of British taxation sans representation. Emphasize the ruling Norman oppression of conquered Saxons that is themed in Ivanhoe, the 1800s Sir Walter Scott book that popularized the Robin Hood character in the first place, and you’ve got a story about racism and intolerance even if Al Sharpton wouldn’t agree ’cause they’re all white folks. That’s why different versions of the story among the scads that have been filmed through the years have been used by their makers to touch different cultural and political nerves.

I grew up watching “The Adventures of Robin Hood,” starring Richard Greene during the 50s without ever realizing its stories about the exploitation of serfs and ill gotten capitalist wealth were written by blacklisted communist Hollywood writers who were spreading Soviet agitprop. Neither did I know that Robin’s paranoia about betrayal to the authorities was what the pseudonymed writers of those stories worried about lest their propaganda jig be up. “The Adventures of Robin Hood gave us plenty of opportunities to comment on issues and institutions in Eisenhower-era America,” admitted writer Ring Lardner, Jr.

“The Story of Robin Hood and his Merrie Men” was also done during the 50s but its maker, the anti-communist Walt Disney, emphasized the ruinous taxation imposed by an oppressive King John at a time when America’s top bracket was 90%.

1938’s “The Adventures of Robin Hood” starring Errol Flynn is the only version I’ve seen that really focuses on the oppression of the Saxons by the French speaking Norman rulers who won the 1066 Battle of Hastings.

The Normans were really French speaking Vikings. And the England William of Normandy and his cousin -- and my ancestor -- Gauthier Giffard fashioned was one in which the Saxons and other subjugated peoples like the Welsh sucked hind teat in ways we today cannot begin to imagine. Against that blackness, robbing those who had taxed the common man to the edge of existence in many cases was both moral and necessary.

Translation of plaque at Castle Giffard, Normandy: "Gauthier Giffard, Lord of Longueville carried the Banner of the Duke William. Departed from this land to the Battle of Hastings accompanied by his two sons, one of whom became the Duke of Buckingham." Over time, Norman nobles started getting the short end of the stick too. That boiled over under the harsh and inept rule of King John (known as “Soft Sword” for his military incompetence) to the point that the barons forced John to sign a bill of rights against absolute royal power known as the Magna Carta. What I’ve never seen depicted is that those rights only applied to the nobility, that John refused to honor them, that he had the leaders of the Magna Carta barons killed, and that England plunged into years of bloody war between the barons and the king. Did Robin Hood really exist? Certainly not as he’s been portrayed — if at all. But that doesn’t really matter, because the real importance of Robin Hood is that he’s an inspiration for taking a stand against injustice however one defines it. --- Dan Gifford is a national Emmy-winning, Oscar-nominated film producer and former reporter for CNN, The MacNeil Lehrer News Hour and ABC News.